The day after our dad died, my mother came into the living room crying.

She said, “He is everywhere I look.”

And while I am very sad he is gone, that statement is very, very beautiful to me. Because our dad wanted to have a life that mattered, that had meaning, that helped people who needed help. He wanted to be everywhere.

Of course, I didn’t know this about him when I was little. When I was little, I actually didn’t like him, preferring only our mother. I was stubborn about this, and I’m sure it hurt his feelings, but it makes a lot of sense; we are both so much alike that conflict was inevitable.

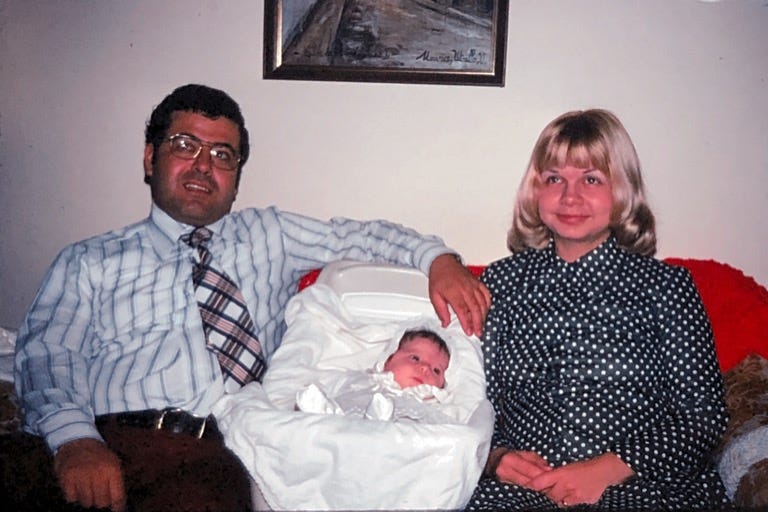

But when I was little, my dad was a man with black curly hair who had the biggest arm muscles I’d ever saw. My sister and I would ask him to make a big arm muscle and ooh and ahh over it. He could carry an armchair down to the end of the driveway over his head, so obviously, he was the strongest person alive. He was gentle and he let us touch his stubble on his cheeks, which we called his “nubs.” He went every day to a job somewhere and wore a suit and he said our mom was the prettiest woman alive. I didn’t know anything was different about him until a girl at church said to me, around age 9 or 10, that my dad had a cute accent. I had no idea what she was talking about. The way he spoke was just the way our dad spoke. That our last name was unusual also didn’t register to me; I heard my mom spell it out over and over again on the phone, as if the person on the other line was an idiot.

Our dad took us on vacation and he mowed the lawn at my grandparents lake cabin and he was photogenic, like my sister, and when all three of us girls took over the upstairs bathroom with our hairspray and makeup and tampons, he retreated to the downstairs spare bathroom every morning to shower. Dad answered the phone “Mesrobian speaking” and he peeled plates of grapefruit for us after dinner and he rode his bike to work sometimes and he watched boxing on a tiny black and white television in the kitchen on weekends, while my mom got the luxurious color TV all to herself. He sometimes called people and spoke Armenian; we sometimes visited people who spoke that to him. He made hummos in the blender and lacumun at the end of every summer when the tomatoes came in and he got hassled in airports in the 80’s when he traveled internationally, since he was born in Syria and customs agents never knew what to make of that.

He liked physical comedy, like John Belushi on Saturday Night Live or Larry, Moe and Curly. In the 1990’s, when Chevrolet partnered with Bob Seger, he would go around singing, “Like a rock” whenever that commercial came on. Which he strangely conflated with another commercial for Cadillac: “Cadillac/Cadillac/Cadillac style.” He would pinch our cheeks and call us “Anousheeg” which mean sweetness in Armenian and that used to bug me, but now I get it. When he called his siblings, he said, “hello brother” or “hello sister” which we thought was funny.

And our dad was actually really funny. Not just in the cheap shot way, where he’d mix metaphors or idioms—he once told me when I was complaining about something I didn’t want to do, well, Carrie, that’s the way the cookie bounces—but also he had a unique way of looking at, well, everything. He wasn’t a silly guy—he destroyed many a joke in his delivery—but he liked silliness in others, especially children.

He encouraged activities in others that he wouldn’t pursue himself: sports, playing the piano or guitar, singing, theater. He walked our dog Cookie every day, not because he liked dogs – he was culturally averse to them in many ways – but because we loved Cookie and he often was able to work out his thoughts about engineering problems while walking her.

I was a sophomore in college when Cookie finally died and there is a little detail about my dad from that time that I think sums him up very well. Cookie was failing and my parents were going to take her to the vet the next morning to put her down. What happened was that after my mom went to bed, my dad stayed up with Cookie. And when Cookie died in the middle of the night, breathing her last on the living room rug, he didn’t wake my mom up. He went to the kitchen table and sat down to write out checks and pay bills until the morning, waiting until my mom woke up to tell her the news. That mundane action always stuck out to me. He didn’t panic or freak out or wake anyone up. Maybe he cried a little, who knows. My money’s on he didn’t. But he just stayed there, and kept steady, and did something useful. Doing something useful was his main coping mechanism.

Because though he was good at seeming calm, my dad was often plagued with anxiety. It was part of why he couldn’t sit still, why he was always working on something, whether for his job or around the house. He worried a lot, and he was serious about most things, and he never forgot that he was very fortunate to have the things he had and the situation he had. He was gravely concerned about people who didn’t have enough food to eat, who didn’t have a place to live, who couldn’t go to school. And that grave concern extended to his family, who he perseverated over deeply. If we were driving in snowy weather. If my mom got sick. If we were getting bad grades in school. If our babies had ear infections. If our furnace might break and kill us with carbon monoxide. If Adrian would get in an accident on his motorcycle. If we struggled with anything, he felt it deeply and obsessed about it. It was the reason he wrote so many letters, putting down his thoughts and advice in print.

Whenever my dad called, it was always task-oriented. He would say something like, “I am mailing you the title for the car; put it in your fire-proof safe.” He was very big on fire proof boxes; we all got one when we became adults, even the grandkids. Sometimes, he had a question about something for me: when was the last time I changed my smoke detector batteries—he liked to give gifts of batteries in our Christmas stockings, actually—had I figured out how to cash the savings bonds he’d given Matilda every month since her birth. Last year, he called to tell me that he was concerned about my credit score and wanted to know my student loan balance, because he was worried that interest rates were too high and that would affect my ability to…do something financial, I guess?

The hilarious thing about this, was at the time he called, I myself didn’t know what my credit score was. That he was worrying about it preemptively, without having the actual facts, was just more proof that retirement is not always a great thing for people. And especially for him.

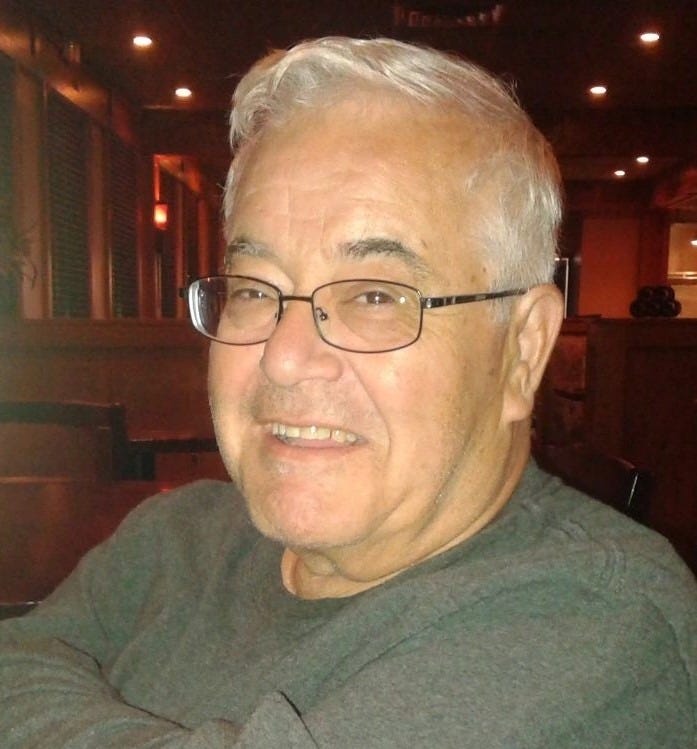

In the last couple of years, he would call me without tasks. “Your mother is having book club and I am at the mall eating a schwarma,” he might say. Then he would ask how everyone was doing and get the latest news. He would tell me all about the book he was reading—everything except the title and the author, because he wasn’t great with remembering names. Then he would tell me if any of the grandkids had written or called him and tell me everything he had learned from their letters or calls or texts. And then—though he claimed he didn’t like Lena, their cat—he'd explain how he kept a spreadsheet of the brands of cat food he bought for her and how he would sleep out in the living room with her because he didn’t want her to be lonely. He would tell me about any critters he caught in his humane have-a-heart trap or the turkeys that came through the yard or if he was going to collect maple sap this year or just skip it. There was always something he wanted to know or do or make or worry about.

I found this little scrap of paper in one of his desks—my dad had desks all over the house, in case he needed to spontaneously break out and design a generator in the upstairs guest bedroom—“Worrying does not take away tomorrow’s problems; it takes away today’s peace.” This didn’t really seem to work on him, though I suppose the many anxious people in our family, myself included, might want to take it to heart.

I am so proud that we were raised by our father. I am glad he picked my mom, because she was able to make life fun for him. I am glad he came here in 1964, with very little in his pocket beyond his dreams and hopes. I am glad that people helped him and took him in and loved him. I am glad our kids were able to know and love their Papa so well, and that he had so many friends and colleagues and loved ones who are in this room today.

I am glad that wherever I look, whenever I worry about my kid or stress about something or read a news story about refugees or hear a corny Bob Seger song, I will see him.

Because like my mother said, though he is gone, he is everywhere we look.

Your dad sounded like a wonderful man Carrie. Thank you for sharing your memories of him, with this beautifully written tribute.

This is so beautiful, Carrie. What a moving and beautiful tribute to a remarkable man who so clearly loved his family so much. Thinking of you. <3