I.

It’s not at all accidental that many creation stories begin with not just the making of creatures and habitats but also with their names.

It’s basically unavoidable. You’ve got to set things up for your reader. Even the lowliest school play has a program listing the cast of characters.

In this essay, I will meander through several different novels and look how the names of the characters create the ambience, the plot and the imagined world for a reader. Naming things is very simple. But that doesn’t make it easy to do. This might be due to the inherent power in giving someone or something a name.

You’re now the god of your own little fiefdom, the mapmaker and chronicler of all its creatures. Respect and reverence, with a little bit of delight, is what’s called for in this task. This is crucial when devising character names, which I will focus on here, but also applies to place names (which I’ll look at in Part II).

II.

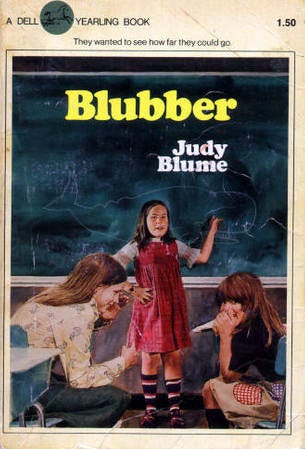

In Judy Blume’s Blubber, the narrator Jill is part of a 5th grade classroom full of vicious bullying against a girl named Linda Fischer. I read this book when I was around that age and it struck me as completely true. There is the world that your teacher thinks they’ve created in your classroom or school, and then there’s the actual situation, which they cannot fully see. The world of school is built of so much more than what the adults positioned throughout it create, which is why it’s such a great place to set a story.

Even better: the name Blume gives the clueless teacher—who seems oblivious of much of the torment and cruelty rained down on her student Linda Fischer—is a name that’s in accordance with her ineffectual, flaccid response: Mrs. Minish.

It’s not a name with a loud sound. It’s about as potent and sharp as the sound your mouth makes while eating peanut butter, which, coincidentally, is the one food Jill can stand to eat when her health-food nut Great Aunt Maudie comes to take care of her and her brother when their nanny goes on vacation.

Mrs. Minish is a really good stand-in for so many professionals who work with kids. It’s not that they’re malevolent, nor is it that they don’t care. It’s that they have only so much capacity, attention and power. Schools are not places where those three things are distributed equitably to begin with, and despite the reasons people go into education, it’s still a job that one must have while also trying to maintain a life like any other.

Mrs. Minish, then, is not someone who will take control of the hostile environment under which Linda Fischer suffers. Mrs. Minish barely seems to notice Linda’s plight for most of the novel, and when she does pay attention, the teacher tends to blame Linda for the situation, instead of the actual kids teasing and taunting. And so, Mrs. Minish is not one the kids go to for guidance or support. Her character arc is built immediately into the plot. She is diminished instantly and vividly, with Blume’s deployment of her name. The kids in the story will have to solve this, or keep making it worse, all on their own.

III.

The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits and Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude have long been taught as companions; indeed, many consider Allende’s novel, which follows the history of Chile through the Trueba clan, to be a feminist response to the male-dominated tale of the García Márquez Buendía family of Colombia.

Both novels use names to build the world and set character arcs. García Márquez has the same first names rattle and repeat through many generations, mimicking the repetitious nature of the violence in Colombia’s history. Both women and men pick up names from previous relatives, thus marking them for similar fates down the line. It’s a kind of spine for the novel, a structure that requires a call and response among the generations.

Allende’s novel uses two points of view; one in third person, from the perspective of all the women of the Trueba family, whose names inform us obliquely the more enlightened view of history. Nívea, Clara, Blanca, Alba: all names that shimmer with literal connotations of clarity and light. The other point of view is from the rich family patriarch, Esteban Trueba. Esteban’s wealth comes from a diminished family inheritance, which he used to work a silver mine in the northern part of the country, to great success. The man’s literal narrative blossoms in darkness, at stark contrast with the light of the women in his life.

Another clever way Allende uses naming is to give the twin sons of Esteban Trueba names that aren’t traditionally strong sounding. Clara determines the twins will be named Jaime and Nicolas, names that, like Mrs. Minish, roll off the tongue in Spanish softly and delicately. Esteban wants at least one of them to be called Esteban Segundo, after himself and his father. Clara refuses; the repetition of names messes up the timeline in the metaphysical journals she keeps. Indeed, both twins live up to the prophecy their names declare and which their father resisted: Jaime becomes a martyred doctor to the poor; Nicolas loses himself in faddish pursuits of the 60’s: health food, asceticism, drugs, meditation. Neither has any interest in continuing the business and legacy their father has built.

Personally, as a reader, I have better recall of the names in Allende’s book; García Márquez’s has so much repetition that only the unusual names of the women still stand out to me: Ursula, Amaranta, Remedios La Bella. Perhaps that’s intentional; the men blunder, over and over, being of similar iteration, while the women have more demarcation, a component of their enlightenment, just as in Allende’s novel. Perhaps the publisher or García Márquez knew the reader might need assistance with keeping everyone straight; most editions of One Hundred Years of Solitude include a cast of characters at the onset, a reference I appreciate having for a story of such scope. Making such a cast of characters while drafting is a useful practice, I’ve found. This lets you see any redundancies in type and whether you’d like that repetition or not.

IV.

Winter’s Bone by Daniel Woodrell

End Zone by Don DeLillo

Another book that I love to think about in terms of its names is Winter’s Bone by Daniel Woodrell. Winter’s Bone, set in Appalachia, features a protagonist named Ree Dolly. Already Daniel Woodrell is sending signals with this name: the one-syllable, three-letter Ree is a stripped down, practical girl, geared toward survival to a degree that belies her age. She’s not a “dolly” in any way. None of the women in this bleak tale are.

Jessup Dolly, Ree’s father, has skipped bail after an arrest for meth manufacture. The bondsman is going to come for his money, jeopardizing the family’s house and the last stand of woods they own. Ree suspects her father hasn’t purposefully skipped out: “Dollys don’t run.” But she needs to find him to keep the roof over their heads, just like she needs to keep food on the table for her younger siblings, which she does by shooting squirrels for stew and making grits that use up the last of the butter. Her mother Connie is a shell of a woman, depressed and incapable of tending to her children, leaving Ree alone to provide for her siblings.

“Where is Jessup?” is the question that resounds through the story. To find out, Ree continues to go out in the harsh cold to ask people for favors they don’t want to give and information they aren’t willing to share. Many of these people share her blood and she can’t understand why they won’t help her out.

There are a string of names in this region that go way back, families twining around each other in marriage and babies and grudges. Woodrell writes, “There were two hundred Dollys, plus Lockrums, Boshells, Tankerslys, and Langans, who were basically Dollys by marriage, living within thirty miles of this valley.” One of Ree’s siblings is another man’s baby, which is a hint at to why Ree’s mother is so shattered. Through the novel, there are tangles of boys named Milton and Jessup, names that portend a hard life full of brushes with the law, misery, cruelty and violence. Ree fears the fates of her younger siblings set in these names and cannot see a way to break the cycle of trauma and poverty other than by leaving—“flying away” to the Army, which will result in the kids having no one to care for them. Incrementally, “Where is Jessup?” fades. What we end up learning, as the novel unfolds, is the frightening uncertainty of “Who is Ree?”

Don DeLillo’s End Zone has been a book I’ve returned to multiple times since reading it in my teenage years. If you’ve read David Foster Wallace or Jonathan Franzen, it’s easy to draw a line from them back to DeLillo. Don’t let that be a reason you avoid this book, though. I’m not really a fan of DFW or Franzen, myself, and unlike some of their novels, End Zone is a tightly packed delight. DeLillo revels in the sheer pleasure of language. Piles of phrases, thick layers of jargon, dense paragraphs of uninterrupted dialogue: it’s unmistakable that DeLillo loves words, and you’ll love them, too, after rolling around with his.

I should also probably disclose that End Zone is about football. But again: it’s not what you’d expect. I’m indifferent about football, at best; at worst, I think it’s monetized destruction as entertainment, which means it will be with us, like cockroaches, after the apocalypse.

Speaking of apocalypse: End Zone is also about nuclear war.

This novel is my favorite kind of experience: weird, funny, awful, intellectual, crude. It takes place at Logos College, a fictional school in West Texas. There’s a sequence of tragedies that befall the football team and the school. There’s a girl who wears a dress with giant mushroom cloud applique. There’s constant pain, hurt and injury—players passing out on sidelines, players having dislocated shoulders pushed back in place, players vomiting on the field, players breaking bones. One player is taking a class on “the untellable.” Though the entire class is conducted in German, not knowing German is a prerequisite.

There’s a lot going on in here, obviously. I like books that are stuffed full in this sense. But what I want to focus on is the way DeLillo chooses names. It’s truly magnificent.

The narrator of the story is Gary Harkness, a talented halfback who has failed out of several college football programs due to his eccentric behavior. The familiarity of his first name combined with the brutality of his last name is a tiny microcosm of what the whole novel is about.

Here are more dreadful, excellent names:

Quarterback: Garland Hobbs

Head coach: Emmett Creed

Offensive line coach: Tom Cook Clark

Defensive line coach : Rolf Hauptfuhrer

Backfield coach: Oscar Veech

Assistant coaches: George Owen, Brian Tweego, Sam Trammel

Head coach of the rival team: Jade Kiley

Rival team: West Centrex Biotechnical

New running back: Taft Robinson

ROTC instructor who discusses nuclear war with Gary: Major Staley

Exobiology professor: Alan Zapalac

President of Logos College: Mrs. Tom Wade, widow of the Tom Wade, the founder

College administrator: Mrs. Berry Trout

The girl in the mushroom cloud dress: Myna Corbett

Myna’s friends, who are sisters: Vera and Esther Chalk

Myna’s favorite sci-fi author: Tudev Nemkhu, a Mongolian author who writes in German

The public relations man, who has managed all-girl rodeos and sword-swallowers on trampolines: Wally Pippich

Then there’s the football roster! A reel of absolute brilliance. The names roll through the story, luxurious and odd:

Moody Kimbrough. Chuck Deering. Jim Deering. Jimmy Fife. John Jessup. John Butler. Dennis Smee. Raymond Toon. Bing Jackman. Vern Feck. Terry Madden. Roy Yellin. Cecil Rector. Bobby Hopper. Bobby Iselin. Dickie Kidd. Randy King. Norgene Azamanian. Anatole Bloomberg. Buddy Shock. Lee Roy Tyler. Champ Conway. Lenny Wells. Billy Mast. Ted Joost. Howard Lowry. Andy Chudko. Larry Nix. Lloyd Philpot Jr. Gus de Rochambeau. Link Brownlee. Len Skink. Spurgeon Cole. Chester Randall. Onan Moley. Byrd Whiteside. Mike Rush. Mike Mallon. Jerry Fallon. John Billy Small. Jeff Elliott. Ron Steeples. Tim Flanders. George Dole. Mitchell Gorse.

What delights me about this rollicking, bizarre list of names is the verisimilitude.

There are multiples and repeats: Jims, Johns, Mikes and Bobbys.

Strange sounds: Veech, Skink, Chudko, Tweego.

Clipped syllables: Fife, Smee, Feck, Shock, Mast.

Cascading, good-old-boy names: Tom Cook Clark, John Billy Small, Lee Roy Tyler. Absurdities: Can you imagine naming a baby Onan Moley? DeLillo knows “Norgene Azamanian” is a remarkable name; he tells the curious origin of this player’s name, before killing him off in a car accident.

Many of these characters are not fully realized. It doesn’t matter. Their names provide an ambience all on their own. They move on the playing field, exiting and entering, bleeding and hurt. They walk around in their jockstraps. They have pissing contests and chug ketchup. They complain about the milk and the meat in the cafeteria. They talk in ways that are outlandish and expository. They play football in the snow until their hands freeze. These names are so good at telling us who they are —I can easily picture Garland Hobbs, a golden blond quarterback, getting most everything he desires, though DeLillo never describes him. He never describes most of the characters; I could argue he doesn’t need to. The names do all the work, which is really work done by the reader. We imagine ourselves into their names, which, in my opinion, is one of the greatest gifts of a novel can provide.

V.

Endowing characters with names is as critical to storytelling as casting the right actor for a film or play is to visual performance. The names we give everything set a tone that the reader responds to, consciously or otherwise. Names offer the reader a foothold for imagination to gain purchase on the narrative.

Before she became idiotically infamous for her anti-trans rhetoric, J.K Rowling was an author I liked to cite for her fantastic work with names. This aspect of the work itself is still alive and beautiful, such a dear part of building that beloved world—Rowling admits to collecting odd names her entire life and this activity clearly paid off.

Apart from her recent nonsensical public statements, this lesson is a good one for storytellers. Those peculiar alleys in life that often cause you to be derelict from your normal responsibilities can yield some exciting treasures.

Character names often come out of our subconscious, along with a whole lot of other weirdness that wriggles out when we invent people and places. This is a fine kind of accident for your mind to make. But it’s important to remember that names are in some ways a prophecy. A baby, or a house, or a place, is given a name. Either it lives up to the name’s lights or it does not. Of course, there are cultures where one earns new names, based on rank or achievement or spiritual gains; as all of us proceed through life, we collect nicknames and titles and such. Generally, though, most names are decreed by others. The degree to which a child manages to outrace their name’s oracular shadow is what juicy stories are made of.

So, you make up one name, and soon you’re making up the names of their ancestors, too. This can escalate in an astonishing fashion. All these imagined people, situated in a cultural context, a time and place, with risk profiles and value systems, begin to emerge and hand out names. Whole generations of parents and caregivers and guardians are streaming back into a time that never was; here is the geography of fiction, here are the markers of growth and death, here are the main players launching forth a child carrying their new, untested mantle: a first name, perhaps a middle name, a surname.

This great unending stream is why it’s not enough to say, “I like this cool name; therefore, my protagonist will have it.” Not just because that’s lazy. But also because it’s boring. It’s your loss, as a creator, truly, to just stop there. Names themselves have roots. Don’t miss the opportunity to dig down into your own mind and see how far they go.

like what I make?

I envy your book-memory. I'm trying to remember the names of characters in a trilogy I read last year...and I'm drawing a blank.