My grief over losing my father has made writing a problem. Writing, words. Stories, even.

It’s this: Telling the story creates a distance in me from the guts of what happened.

Because in the telling of it, I’m not feeling the emotions I had in those moments where I held my father’s bare feet, touched his clubbed toenails that signified the lung disease that killed him. Not feeling what I felt when I realized we have calluses in a seam on the same part of our feet—indeed, the same size feet.

In these sentences, I’m not feeling anything. I’m writing for you, considering what facts you need. I am setting a plate, portioning out bits, creating a consumable meal so that you may sit and eat. Emotionally, this has little to do with me. It is a message I am carrying. The carrying lets me forget momentarily how much it hurts to recall those final weeks. How I made my own unsung narratives on drives to hospitals and hotels. How I was irritated and tired and hollowed out by fear, by the sheer magnitude of loss we might come to know. Are still coming to know.

The telling of the story lets me pretend I’m in charge. Lets me think about your reaction to it instead of my own. Lets me resuscitate this man, this beautiful, infuriating, anxious, brilliant man, blowing into your life the breath of him. A desperate bid to re-inflate him. Pretend he’s still here.

Imagine me, trying to do that. Sweating over a giant bellows, exerting myself to avoid the pain I feel from the moments it took for him to die, the fear I have of my own death, my own black hole of responsibility and uncertainty about if I can carry what he carried for nearly 80 years. As if I could ever do it. As if I should.

Instead of sitting with that, there are sentences. To entertain, to explain, to emotionalize.

And it seems benign. Even helpful. I have so many questions and notes I could share—and there are enough people I know who have experienced this kind of loss. We could all learn something together, right?

Am I tired from grief or from all the new tasks I inherited when my father died?

When will the regret come?

Why am I reluctant to throw away old peanut jars where he kept his change, sorted by penny, nickel, dime, quarter, to give to his grandchildren?

Why am I crying when I hear Charli xcx sing “I will always love you / I’ll love you forever” because: what did my dad, born in 1944 in a refugee camp in Aleppo, Syria, know of British club music and ketamine?

My tears say, stubbornly: But I will always love him.

And I will love him forever. A forever I realize is not eternal, but only as far as the perimeter of my own breath takes me. Forever as far as I’m concerned.

II.

There is now, instead of my father, the package that was his life. It has length and width, his life. No more can be made of him, by him.

Why is knowing the precise circumference of his days so difficult? It strikes me as infantile and basic—banal, even—how unbearable this fact is.

Once, a therapist I saw said that when humans say something feels unbearable, they are not giving themselves enough credit. It’s misleading, as anything a person claims to be unbearable is technically bearable, as they are alive to discuss it—the unbearable thing did not cause death.

But my father’s last days were marked by the unbearable. Meaning, the condition of his body and the mechanisms crucial to keeping him alive were no longer bearable for him. So, he told us he was done. He said, No more. He chose to die.

They gave him drugs and removed the equipment and we all surrounded him, touching him, holding his hands—I held his feet. It took eight minutes for him to die, Adrian told me later. I didn’t notice at the time, because I knew my dad was facing the depth of what came next, and that dented the notion of time for me, I guess. The damage of which still persists.

My father said, Yes, open the door, I cannot bear this. We watched him decide this the day before. And the next morning he walked through it and was gone.

III.

A British pop star is making me cry in traffic. There is nothing I can do about this crying. Or death, either. This happens; there is no argument.

Funny, because I argued with my father constantly. But when he said he could not go any further with us—I’m sorry to leave you, I love you all so much, he said—I did not argue.

I said, Okay, Daddy. Whatever you say. We’re here with you. We love you. I love you.

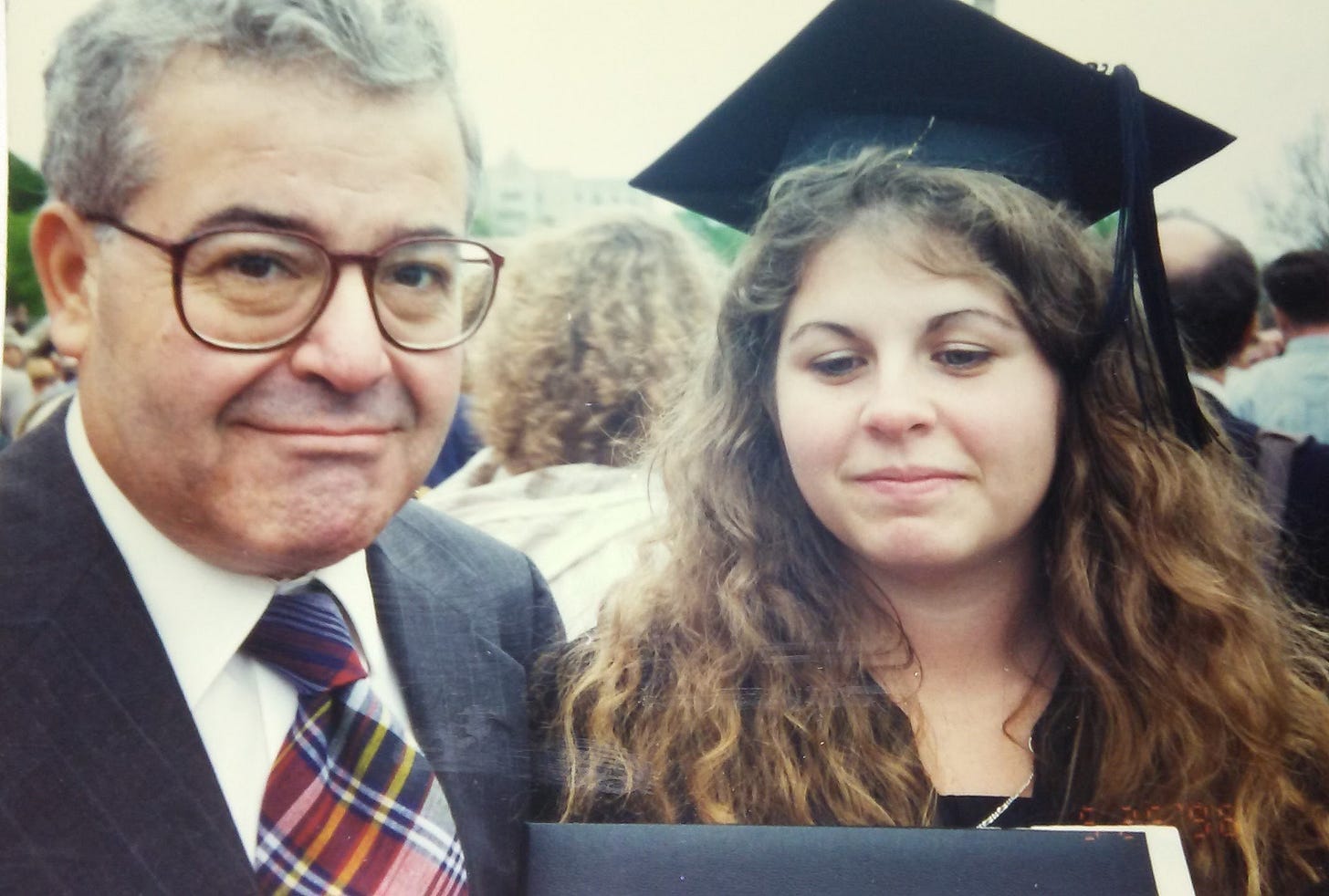

And since that eight minutes, since we left his body behind in that cramped, ugly, too-warm hospital room—where I didn’t want to leave him, where I took pictures of him, his face and hands and feet, the last bits I could get from him, and still it was not enough—I have been running into the next half of my life. I turned 50 years old just days after he died.

In this next half, I have made lists. Made calls. Done errands. Walked in the forest behind my parents’ house looking for mushrooms, because I couldn’t bear what I must do, what I couldn’t argue about—funeral lunch catering, obituary editing, photo arranging, remembering, comforting, taking out trash, bringing in mail, paying bills, stopping cards, scheduling meetings, making decisions. Always moving.

I am so tired. Too tired to shape these words into a proper form. An obituary is just a draft, one way of thinking how a person’s whole life might signify, at a point where you are still being fitted for the garments of grief.

I feel unable to enjoy things and unable to argue about that, or advocate for what I would like instead. Words are hard. To read, to write. They seem like a sin. My entire life, I’ve used words, spoken and written, to do so many things: to hurt people, to be abrasive, to laugh at things, to soothe myself, to escape my body, to reveal my own secrets, to reveal what was not mine to reveal.

Maybe what I need to reveal is just how lonely all this feels. I don’t know if my father is lonely—I feel like he is not. But I know my mother is, and that absolutely guts me, her loneliness. At the same time, I feel that I deserve loneliness. As a season, a rite to mark who and what we’ve lost. Since I’m unsuited for public consumption, it seems natural to punish myself. To resign myself to feeling everything bad now, just fucking feeling it—in my body, in my bones, unmediated by ink and language and perspective and metaphor.

But then—I can’t help it. I have to write something down. I don’t have to edit it, though. Or organize it. Or try to beat the meaning out of it with a rubber hose, to paraphrase Billy Collins.

I am watching everything go on. Living, rusting, blooming, wilting, stretching, cracking, cycling. Maybe that also hurts: knowing all that vivid growth is still happening while inside I am as hollow as the great maple in the woods behind my parents’ house, the one that cracked after a lightning strike and snapped weeks later into the ravine, surrounded by moss and the last of the periwinkles.

This was gutting and beautiful. Sending you so much love, Carrie.

Thinking of you, Carrie.