I.

Let me start with what I can accept. Eyelet. I love a garment featuring eyelet embroidery. I can’t explain why; it’s intricate and femme and fussy. But I find the bulk of eyelet, the dedication involved in its creation, to be impressive.

Last spring, I bought several eyelet skirts in white. I dyed some of them with Rit dye. Green and blue. They turned out fantastic. They became my summer go-to, as I loathe shorts (upcoming essay). The skirts themselves were minis, short flippy things, with a cotton lining that ensured you couldn’t see my big dumb underpants through the eyelet. They were also very cheap: I bought them with a bunch of coupon codes and the per unit cost was about 17 bucks.

I also own several white shirts with varying eyelet patterns. It’s the one bit of romance I appreciate in clothing.

This is top of mind because a few days ago, I found myself ordering more eyelet skirts. These ones were longer, a kind of midi length that will be a maxi length where my body’s concerned. I’m really excited to see what they’re like in person. I think they’ll be great pieces: I bought blue, black and white. I might dye the white. I might wear the black and blue in winter. I might embroider around the eyelet to add some color. I love how they will cover my entire leg area so I won’t have to shave. I can be all formal, like Frida Kahlo. Possibilities abound. Stay tuned.

But eyelet is the end of the line when it comes to my tolerance for clothing that could be termed “romantic.” If it has ruffles, puckers, pin-tucks, pleats, smocking, shirring, sequins, appliques, rivets and grommets, balloon, bell, flutter or puff sleeves, a series of cloth-covered buttons climbing up the wrist, a racerback made of lace, a yoked collar, lacings, bows, tassels, fringe, pleather patches or any combination of the aforementioned tomfoolery, I’m not having it.

II.

Everything starts in the body. Every single thing you believe to be true has been confirmed by you, through your body. Consequences of this can be bad or good or a little of both.

One bad one: if all the bodies you see wearing the clothes that are available for purchase don’t look anything like your body, which is true in my situation, you may assume that your body is defective.

In my case, I am a short, compact woman. I am sturdy. I am husky. I am stout. I am plump. I can barely type any of this, as it’s so embarrassing to say, though that’s ridiculous. You can see me, after all, and I can see myself. So many people assume that those of us who struggle in our bodies don’t have mirrors. I have a mirror. Trust me—I know what’s going on.

I have always been, more or less, going through life uncomfortably, sometimes with horror, other times with shy dismay, when it comes to my body. I’m 46 years old; this seems like something I should have conquered by now. But I haven’t and there are good if not banal reasons for why. I’m lucky that there have been some rather lovely people in my life who have made me feel, on occasions, that the skin I’m in is fine—more than fine, desirable, even. I’m also lucky that in the last twenty years, I’ve done some pretty cool things with my body, and none of these were in spite of it, either. So, it could be worse.

But it could be a whole lot better, too.

This trouble with my body? It’s probably why I like writing and reading so much. Both can create identity and connection in a disembodied way. People can view me and value me for reasons independent of my physical shell.

But the truth of the matter is that I don’t enjoy being in my body most of the time. I’m annoyed with it, impatient with it, disgusted by it and tired of it. And yet, I must tend to it, feed it, heal it when it gets ill, and, unfortunately, clothe it.

This is where my problem with frippery emerges.

III.

I used to have size 40H breasts. They didn’t come out of the box that way; pregnancy caused them to reach that size. But they were big to begin with, and that beginning came in 4th grade. I was essentially mobbed by runaway breast growth as an 8-year-old. About a year later, I got my first period.

All of this? Was a huge bummer. I was still a little kid who played dress-up and kickball in the street and had a club that met in my backyard treehouse. I didn’t need maxi pads or breasts. All of this early development meant a bunch of secrets and extra garments and embarrassment and, yes, lots of teasing, from both friends and strangers. It sucked.

About a decade ago, after my breasts failed to deliver milk to the only baby I’ll ever birth, I decided to nuke the useless fatbags back to the Stone Age with a reduction surgery. The surgeon removed 4.5 lbs. of tissue, resized my nipples and, though covered in scars, made my entire chest area much more proportional with the rest of my frame. This was probably one of the best choices I’ve ever made in my life. I could run for the first time; I ran two half-marathons. I can buy bras at Target. I can go without a bra! I can wear tank tops. I can buy swimming suits. It has been life changing.

But. I’m still in my same body. I’ve got a high waist and short legs and a butt that sticks out and, while smaller, yes, a not-insignificant rack. I’m short, so I get absolutely no advantages when it comes to putting on an extra 5 or 10 pounds, like a taller person might. And thanks to my genetics, I tend to put on weight.

Additionally, I have giant, unruly curly hair. It’s EVERYWHERE. I love my hair, actually; it’s probably my favorite feature. But it precludes me from ever looking sleek and tidy. I always look like someone who owns expensive camping equipment, probably has more than one bong and traded backrubs for veggie burritos in the parking lot at Grateful Dead shows. None of those things will ever describe my actual preferences, unfortunately.

But the “too-much-ness” of my appearance is why I want clothing that is simple. I’ve got enough going on already. I don’t need more flimflam hanging off me. I could take Diane von Furstenberg’s advice and further it: get completely dressed and take off more than one piece of jewelry. I could never do Madonna’s Desperately Seeking Susan-era look: ten million rubber bangles and multiple belts and a headband and earrings and leg warmers and fishnet tights and high heels and rips and gathers and gloves and sunglasses and a newsboy cap—no.

I want only the essentials in my clothing. Clean lines. Straight seams. One basic color, possibly a print of minimal colorways. I want symmetry in my necklines, whether vee or boat or square. Swiss dots are the only dots I can bear. See-through fabric makes me ask for a refund. I can’t do anything purple, yellow or orange.

If I could? I’d take all those off-the-shoulder tops, handkerchief hem skirts, paper-bag-waisted jeans and short-sleeve shirts that button on the deltoid and set them on fire while witches and wolves howl in the night sky.

IV.

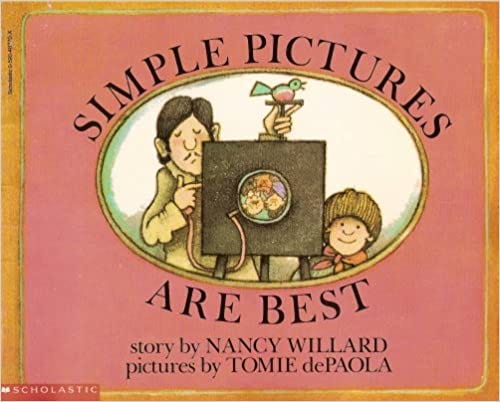

My sister and I grew up in a house full of books. Our mother was an elementary school teacher, and a reader; she knew the value of having books around and reading to her children. There was a book my mother read to us, that my sister still has, that we read to our own kids, called Simple Pictures Are Best. Written by Nancy Willard and illustrated by the late Tomie dePaola, the story is about a shoemaker and his wife, who hire a photographer to come to their home to take their portrait for their wedding anniversary.

Once in place, however, the couple starts to doubt their presentation. What if it’s too boring to just stand there, as is? Shouldn’t the picture reflect their hobbies and talents?

The photographer drily remarks, Simple pictures are best.

But the couple run around in search of props to make their portrait more interesting. The shoemaker fusses over what shoes to wear and after a while, grabs his fiddle and props one of his paintings against his knee. The wife dithers about which hats to wear and decides to set a freshly baked pie in the shot, along with the spoons she plays and a prize Hubbard squash from their garden.

This all looks as you might expect: deranged and terrible.

The photographer repeats himself: Simple pictures are best.

The couple doesn’t listen. Eventually, a bull gets loose from the nearby pasture, knocking over the photographer’s camera at the critical moment. Despite all the foofaraw the couple has accumulated, the photo at the end isn’t of them at all. When the shutter snapped, what is captured is a close-up of the irate bull’s snout.

I loved this book as a little kid, and I love it now. I love how excited the couple gets in their desire to mark the occasion. I love the photographer’s assistant, a boy named James, who stands on his head and juggles turnips when the couple, stiff and uncomfortable in their poses, cannot manage smiles.

I love the idea of taking photos with all your favorite things, of celebrating all the good things in your life. I love all of this—in theory.

Because I hate being photographed. I hate posing. I hate the idea of excess, on my body, on anything that is just trying to be good enough.

Designer Vera Wang, whose clothing and wedding dresses feature a stunning simplicity I’ve always loved, summed up my feelings perfectly in this quote:

I want people to see the dress, but focus on the woman.

That is what I want my clothes to do, too. I want clothes that aren’t going to make you just look at me. I want them to help you to see me. Anything beyond that is just, well— extra.

like what I make?