I.

We have all seen the advice, many times, from many sources:

To be a writer, you must read.

Read widely. Read high and low. Read often, in and out of your chosen genre. Read poetry and textbooks on astronomy and cookbooks and short stories and ancient Greek plays. Read children’s books and biographies and anthologies and academic treatises. Read essays and analysis and articles and newspaper stories and magazine features. Read pulp novels and fairy tales and classics. Read books you think you’d hate and that are hard to read and books you know you love and that are as easy to read. Read, read, read.

It’s kind of boring, exasperating advice. Not glitzy like other pithy slogans—always end a chapter on a question, use active verbs over adverbs, put your characters up a tree and throw rocks at them. Read? Jesus, I KNOW, the whole audience thinks, when you’re on a panel and someone asks the “what’s your advice?” question.

But like many things that aren’t sexy or provocative, they are unbearably crucial. Reading is really the whole thing. The only thing. Your reading habits, in my mind, are the only writing tool that you have any control over. You can produce many, many words, tons of stories, piles of essays. You can put your “butt in the chair” and plot and pants your way through reams of copier paper. You can write and edit and revise and rewrite constantly but there’s no guarantee that output will be anything that is good. OR anything that can sell. (Sadly, there’s a difference.)

Being prolific and productive with your word count doesn’t guarantee anything. People may not like your sentences. People may not like your notion of what makes a story a good time. People may dislike your very take on reality. People may never publish you or pay you to write a damn thing.

And publishing, as an industry? Tends to be a daft, fickle business that rewards a lot of asinine effort. You can’t control that, either.

You do have control, however, over the landscape of your mind. You control what you put in it and this can affect what you produce.

So, in addition to telling writers to “read” I would add: “Read with an intentionality that drives you toward pleasure and curiosity.”

This kind of reading is its own personal reward. At the end of the line, when you’re wrinkled in your rocking chair, this type of reading life gives you the solace of possessing a brain that’s been put through the paces. Who wouldn’t want a beautiful inner landscape, thick with creamy intellectual delights you can share, in print or dinner table conversation, with others?

But you don’t get this kind of brain if you don’t read widely and deeply. And this kind of brain is one that contains the fertile loam for diverse roots to connect across the galaxies that make up your cerebrum.

These roots make stories and images and phrases that resonate and clatter and stick with readers. That’s the goal. The real prize.

II.

Okay. But—what about money?

Well. I, too, like and want money. But, if you read publishing deal announcements, you can see that lots of books are acquired on terms that have nothing to do with literature, even commercially popular literature. For example, you might see something like this in your average deal announcement:

“…an apocalyptic Star Trek: Voyager meets Gilmore Girls on the roller derby rink!”

“a steampunk Dr. Who meets The Goonies crossed with How I Met Your Mother!”

People are paid actual money to produce books with premises like this all the time. Sometimes they are given the premise and paid to write to spec. I realize that’s depressing for some of us to hear. I also realize that these types of announcements are made to attract television and film people, who ostensibly swim in such visual oceans. But plenty of people have used that type of shorthand to create their next project. You can use it, too, if you think it might work and if such mathematics appeals to you.

I think that there are lots of ways to make money. A lot of them don’t invoke your complex cerebral efforts. I happen to be in the spoke of my writing career where I think it’s easier to do an unrelated day job, peddling pablum for marketing departments in corporations instead of throwing in with the Creative Writing Industrial Complex: the online essay farms, the lecture and conference circuit, the ghostwritten chapter book hamster wheel, the low-residency writing program professor, the developmental editor track. Being versatile has its purposes for all writers, and while I enjoy teaching, it’s a labor-intensive job best done by people who can offer ample encouragement and enthusiasm and guidance. And there are times when one must follow the money or preserve personal energy or pull back for their own creative projects accordingly.

Plus, at core, when it comes to reading, I’m kind of selfish. I want to read what I want to read, for purposes that are solely my own.

Which brings us back to reading habits.

III.

How and what I read

99% of what I read is from the library. I don’t buy that many books. This might be shocking—I’m an avid reader, the target customer of publishing, really. I read widely and deeply and every single day.

But I can’t afford to buy everything I want to read.

I certainly can’t store it all in my tiny home.

And I hate e-readers.

I only buy books if:

- returning them gives me a sad, longing ache

- I’m certain I would want to teach from them in a class

- they’re titles that I’d love to loan to friends

So, this means I visit libraries at least once a week, to drop off what’s due and pick up what’s just come in for me. In fact, much of my week’s schedule is arranged on such comings and goings.

I’m always making notes, on my phone or on little scraps of paper, of books I want to read. Titles I hear about from podcasts, from magazine and newspaper articles, from social media, from friends and family. I’ll read a biography of an author and then want to read all the books referenced within it, too. I scour bibliographies for sources as well. I’m a giant geek about these things and always have been.

Why I read: Nonfiction

In general, I read more nonfiction than fiction. Partly because I have trouble sleeping and it’s much easier to relax and drift off to nonfiction. And partly because I just like learning stuff. Nonfiction is where I follow my nose and select topics without much forethought beyond “hmm, that sounds interesting.”

Here are some nonfiction topics I’ve read on extensively: wolves, opiate addiction, malaria, mosquitoes, Latin American history, Russian history, Irish history, Western Medical history, the city of Venice, American mafia presence, murder cases, linguistics, war memoirs, elephants, mushrooms, pottery, food writing, cults, sex, ancient Greece and Rome. These are fairly common interests, thankfully.

This type of reading is pure science for a writer. There is no point to it beyond the pursuit of your desire and curiosity. There is no telling where this information may exit the storehouses of your mind and enter into something you write. There is no research need, no ROI. You are simply interested in things you are interested in and so you collect the books on the subject and read them.

Of course, curiosity doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Curiosity originates in the dungeons of your psychological core, banging its cup on the bars and insisting on a meal. You continually seek answers to questions you don’t even realize you have asked; there is always a root to these pangs of wonder. But you generally cannot see this until later, if ever. I am completely resigned to this opacity, as it gibes nicely with my sense that reading is a pleasure, which feels good and, therefore, is good. Curiosity, in my experience, also feels good. So, I give it free rein entirely.

Why I read: handrail texts

When I’m first building up a story, I have learned to use companion texts as guides as I create the fictional world. I tend to open a story with an image or a single event that a character experiences; I never start with a plotline or a bunch of action. That comes later and it’s not easy for me.

Which is why, when I have friends or my editor read drafts, I’ve learned to listen to them when they compare what I’m writing to other books. There’s so much to be gained if you take a moment to examine these other texts and see if they have an interesting roadmap.

I think of these books as “handrail texts.” I’m not a writing a reprise or a retelling, per se, but I’m using them as something to hang onto as I go up and up and up into the unknown of whatever the hell I am doing.

(I don’t know what I’m doing a lot of the time.)

Sometimes this handrail text is completely hidden to the reader. Sometimes it’s mentioned explicitly. I always part company with the handrail text, eventually, but its influence is always there for me.

Why I read: historical romance

When I’m pressing hard to finish a book for a deadline, I read lots of historical romances. There are two reasons for this. One, I enjoy them, and it feels good to read them after a long day of work. Two, they have nothing to do with my own life or, usually, the lives of my characters. In this regard, a good regency romance offers me the chance to turn off the craft-building machinery in my mind. At least, somewhat.

Because romance novels center human sexual relationships, they tend to encompass the same multitude of experiences in which people find themselves. However, the genre has its traditions and one of them is a return to wholeness or harmony at the end, where the lovers find themselves united, their paths clearer, their goals amended to include a joint adventure.

Which is a long way of saying that romance novels have “happy endings.” I could have just said that, but people assume this means these books are easy to write and silly. They are not, by any stretch, but that is another topic for another day.

What is helpful to me, personally, about the happy, resolved ending is that it gives me endless instances of conflicts and their resolution. Because I don’t tend to write endings that are happy. I tend to end my books on unsettled, teetering points.

I also tend to want better outcomes for my characters. So, I’m fighting in some sense, against what Charles Baxter called “the over-parented character,” who might struggle here and there but ultimately makes out okay, whose arc is known and expected. My desire is to write a story that pivots and swerves from what’s expected. To avoid the united, harmonious ending. To leave strands hanging and dangling.

Why do I have to read romance novels to keep the front of mind? Why can’t I, say, read The Oresteia, or Proust or something staider and more classic, with a less lurid cover?

I could. And I can. And I have.

But when I’m working hard to finish something, at the end of the day, I am a tired creature. I want to lie back in bed and enjoy watching fake people tussle and tangle and ultimately have sex. This format keeps my attention and appeals to my base animal side, all while running a background program directive at the same time—avoid resolution, avoid the expected, leave room for surprise.

This doesn’t always work. Sometimes I send my story and its occupants down a path that I don’t see right away for what it is. Soon enough, I come to realize that it’s a happy ending, the thing I think my characters deserve, the thing they want but probably haven’t earned. So, I double back and try another road. Sometimes you don’t know what you’re doing until you’ve done it.

IV.

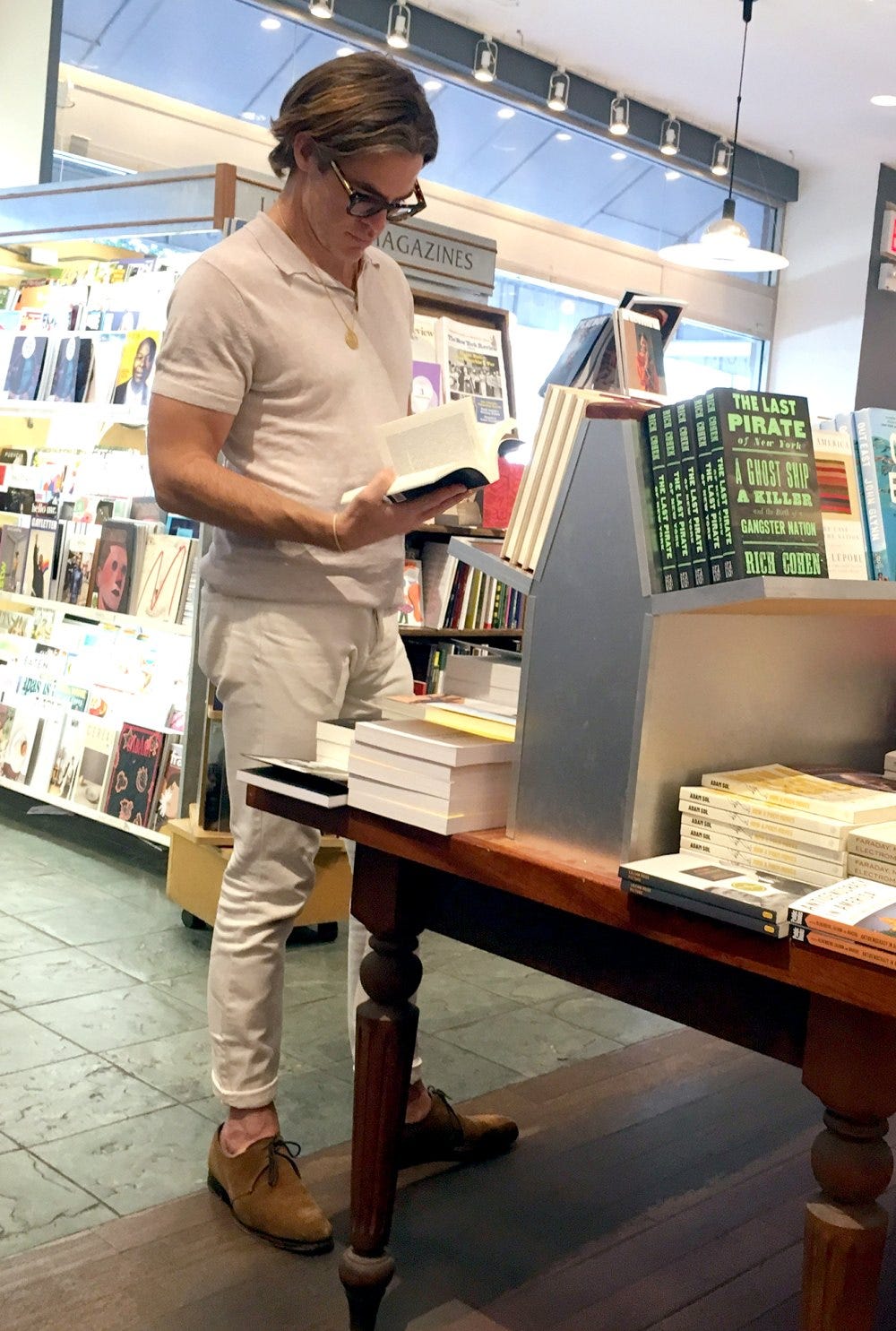

If this case for intentional reading doesn’t move you, perhaps we turn back to money? The simplest way to promote reading is to be a reader. Talk about books, be seen reading books, spend your money on books, circulate the contents of your local library. If we want publishing to expand its market, we need more people who demand its wares, starting with you. An expanded market means increased profits, which means more stories can enter the world and more brains can expand with potential delights. When scaled up, this is transformative.

As Albert Schweitzer once said, “Example is not the main thing in influencing others. It is the only thing.”

like what I’ve made?

subscribe below

www.carriemesrobian.com