I.

I have trouble writing craft essays, I’ve learned, so this one will be short. I suspect this difficulty is due to my core belief that you cannot really teach people how to write. You can only persuade them to see the joy in writing, and then encourage them as they do it.

Truthfully, I don’t really care how people approach their writing. It’s similar to sex. With a couple outlier exceptions, I’m uninterested in dictating how others manage the act of love. Similarly, I don’t really mind how others find their way into story. Do what you gotta do, the world will continue to turn, let us all go on with our rat-killing.

Probably why I struggle to write craft essays is because of this ambivalence. I’m personally fairly allergic to advice as well. So, I will endeavor to be descriptive over prescriptive.

II.

I started writing by writing poems. From second grade through my undergraduate years, poetry was my focus. Sure, I also wrote stories from a young age, but I associated stories with failure, as I never finished any of them and they tended to be derivative and embarrassing to read months after my original fury to scribble them down.

In college, I created a metaphor for why I preferred to write poetry: I compared my words to sheep and insisted I couldn’t be relied upon to mind too many of them. Novels felt unmanageable, nearly reckless, thousands of words all requiring precise selection in terms of sound, style, connotation and denotation. Always one to dream small, I remained firm in shepherding a tiny flock, never more than 100 words to care for and curate. I carried this opinion through my undergraduate years, though my beloved professor Jim Heynen said something off-hand that stuck with me:

“Sometimes, poets discover they have a novel inside them.”

Nearly 15 years later, that idea bloomed into action. I figured, as someone without a traditional English degree, I hadn’t really studied fiction properly. I knew that if I was given the scholastic space, I would rise to the occasion and create something good. Mindful of the $5 checks and contributor copies poets were rewarded with, I figured I didn’t have much to lose.

III.

The funny thing is, I approach writing novels the same way I wrote poems: with a singular, inciting image, sometimes wrapped in an intense emotion, sometimes not. I’d build whole poems around this image, every component expanding out from it: title, epigraph, line breaks, diction. Maybe 100 words, maybe less. I was not a wordy poet; I liked to keep everything to one page, never more than two.

To explore how this would work with a novel, I’ll use something banal as the inciting image: raindrops on rose petals on a windy spring day.

So.

Setting gets established by where the rose bush was planted and when it began raining.

Characters spring from those who planted the rose bush, who admires the flowers, who passes by cutting their hands on the thorns, who plows over them with a lawn mower, who walks a dog who pees on said bushes, who opens up a window and starts hollering to get the dog off their lawn.

Plot comes from the planting, admiring, cutting, mowing, hollering.

Point of view emerges from who I feel most allied with in terms of those actions (or who I can’t imagine feeling allied with).

Theme might be the confusion that growth causes—the same spring weather that brings new life also batters tender shoots with wind and hail.

Motif? The rose, the rain, the thorns, the mower, the dog pee—all qualify.

IV.

So, this is how I build a novel, with a singular inspiring image. I can’t speak to whether this would work for short stories. I’ve never been able to write a short story well; I’d rather write an 80,000-word book than a 5,000-word short story.

Sometimes, the inspiring image will come to me while reading a poem someone else wrote, or while listening to a song. Great songwriters tend to launch me into musing about human frailty and physical delight. These inciting images often appear when I’m taking a walk, or a long drive, or doing something physical (running, swimming, riding a bicycle). Those are really exciting, delicious moments.

The process of building an entire story around one singular image is not linear. It doesn’t come with a sturdy scaffolding. I’ve started many stories that I’ve abandoned half-built. And you won’t be shocked to learn that my weak area is plot; plot always involves the most rigor and thought for me. For this reason, it was a good choice to formally learn in graduate school what makes a story move, what keeps readers engaged.

Writing poetry is conducive to an expansive, slow-motion marveling. I love how fiction as a form also can stop time, enhancing and stretching the present moment with a memory from the past or a note from the future. I love stories that offer up this slow-spinning, luxurious joy. It pleases me that each of my books features these tiny image jewel boxes to share with readers.

I haven’t written any fiction this year. And I did very little last year. But I think if I’m patient, if I keep moving and listening and waiting, something fantastic will surely come.

like what I make?

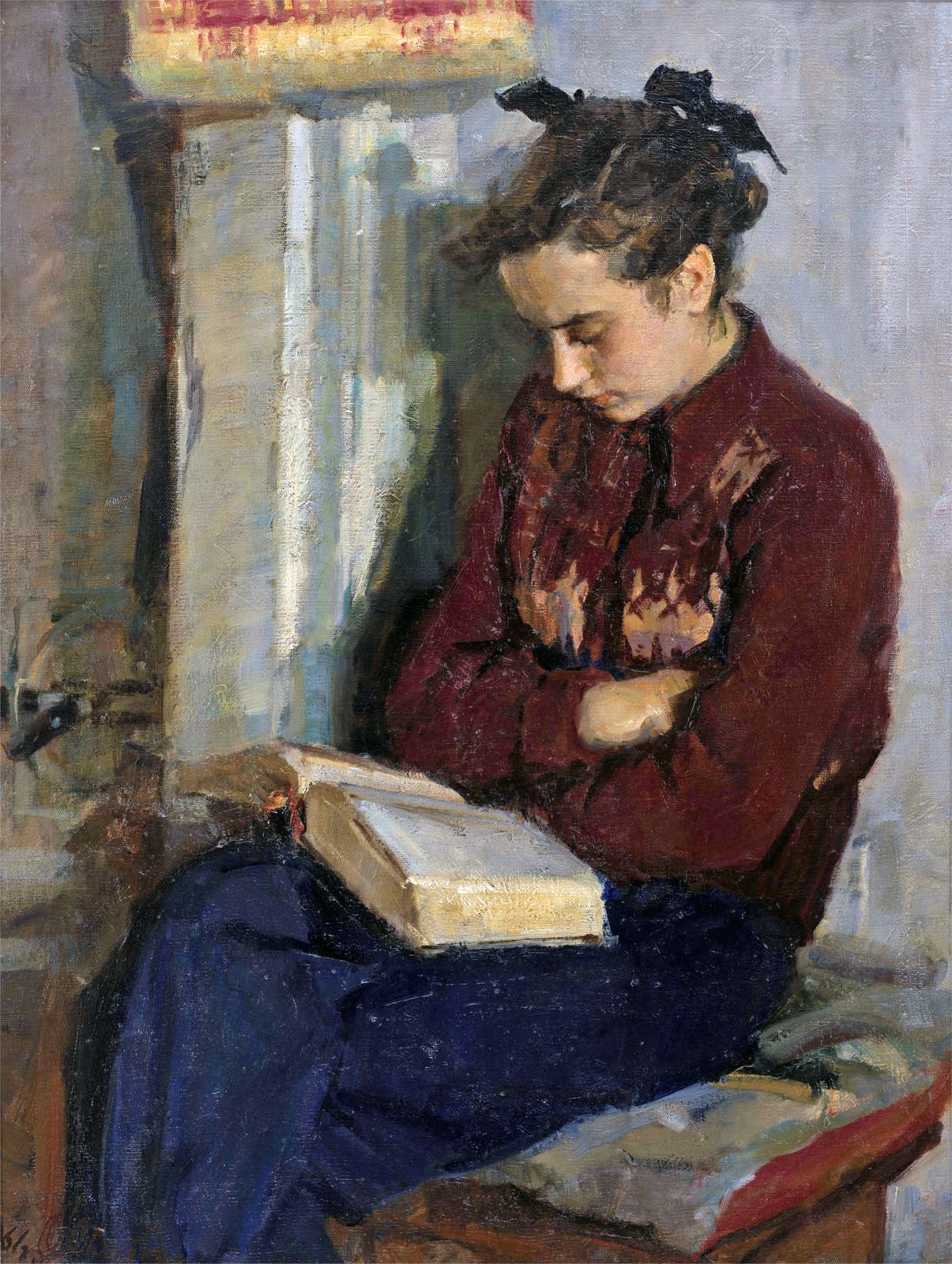

I really enjoyed this blogpost/ essay and shared this with my two writing groups. Some are poets, some are novelists and some are memorists. . .and drum roll some all three! I love your way of thinking. Being. Writing. Oh, and cool paintings of Woman with Book. AnnHursey